It is the eyes of this child, innocent and dumbfounded at how quickly everything is changing around her, that allow the author to put a face to the price of freedom and the difference between integrity and fundamentalism in Persepolis. Like the original Marjane Satrapi, her alter ego on paper experiences for four years what it means to live as a laywoman under an authoritarian and theocratic regime until her parents send her to study in Vienna.

Advertisement

Like the original, the Majane of the comic will return to Iran in 1988, moved by nostalgia and a certain recovered faith, and will find a country in ruins in the middle of a war with Iraq that considers her a Westerner, she who has always been an Iranian in Europe. In 1994, they both surrender to the evidence and settle in France, where the author has lived ever since.

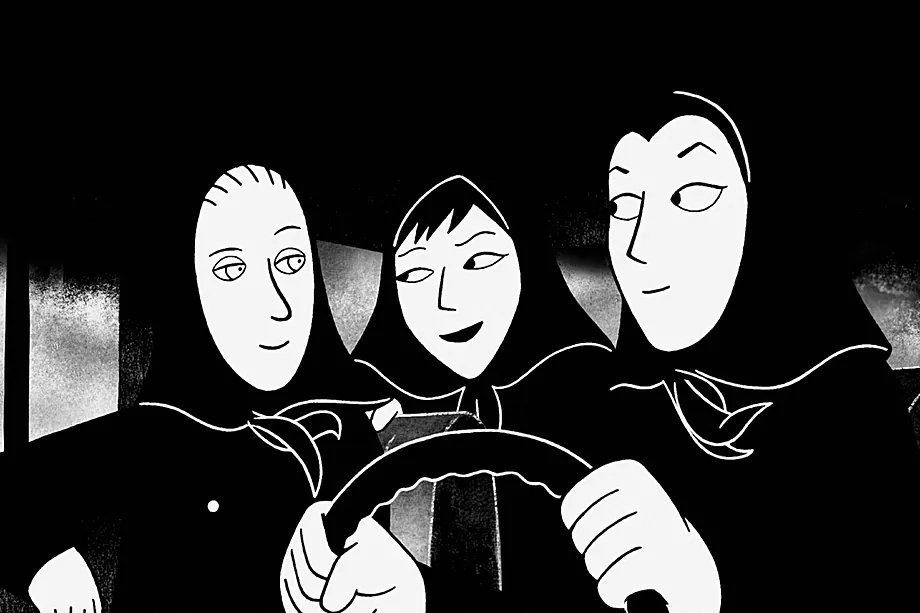

If the comic generated conversation after becoming a publishing phenomenon, what really launched Marjane Satrapi’s message was Persepolis, the French film she co-signed with Vincent Paronnaud, which was nominated for the Palme d’Or and won the Jury Prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival. Its arrival in theaters around the world came as a bombshell in Iran, where the regime only allowed the broadcasting of a censored version of what it considered “an unreal image of the consequences and achievements of the Islamic Revolution”.

Persepolis was also banned in Lebanon for a few weeks at the end of March 2008, before the controversy aroused by the censorship among the population forced the authorities to lift the ban.